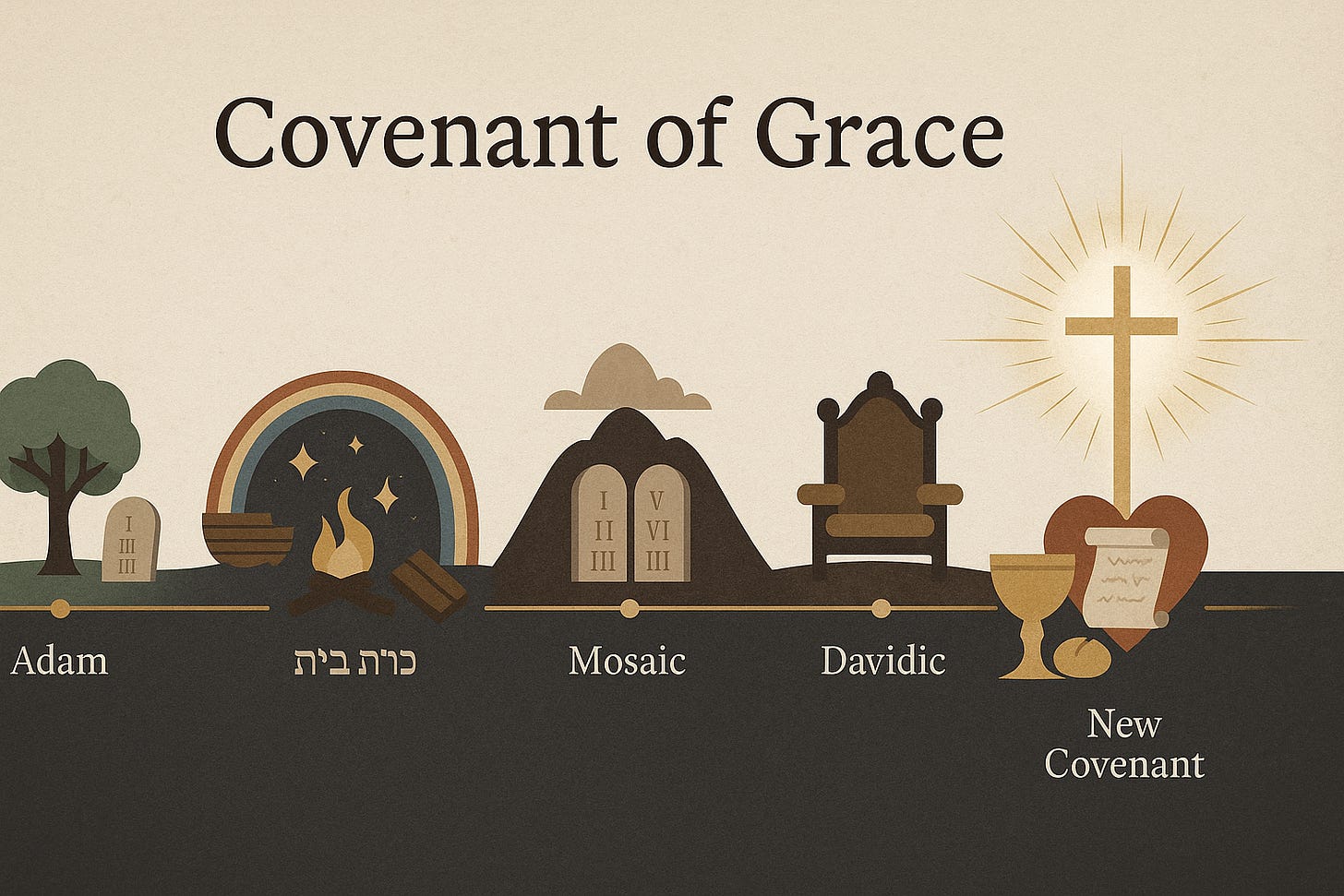

The Covenant of Grace

On Substance, Administration, & Covenant Membership

Membership within the Covenant of Grace has always been, is, and will always be reserved for the elect alone (John 6:37–39; Ephesians 1:4; Romans 8:29–30).

Defining Grace and Covenant

Let’s establish a basic understanding of two terms: grace and covenant.

Grace is unmerited favor (Ephesians 2:8–9; Romans 3:24). However, not all grace is identical. Not every form of grace justifies sinners before a holy God.

The grace shown by God in sending rain upon the just and the unjust (Matthew 5:45) is truly gracious; humanity does not earn this favor. Yet, it is not the type of grace that justifies sinners before God (Romans 3:24–26).

God’s condescension to establish a covenantal relationship with Adam (Genesis 2:15-17) is genuinely gracious. However, this condescension alone did not secure Adam’s eternal fellowship with God (Hosea 6:7; Romans 5:12–14).

Much like grace, the term covenant can be used in various ways (Genesis 21:27, 32; 2 Samuel 7:12–16).

Types of Covenants

There are covenants between human parties, covenants between God and humanity, and the Covenant of Redemption among the members of the Trinity (1 Samuel 18:3; Genesis 9:8–17; John 17:2, 6, 9, 24; Hebrews 13:20).

Each of these covenants involves a different Ranking and represents distinct types of covenants.

Covenants may exist between equals or between a greater party (e.g., God) and a lesser party (e.g., humanity), reflecting a hierarchical Ranking (Genesis 15:18; Exodus 19:3–6).

If covenants have a different Ranking, they are distinct covenants. For example, Solomon’s covenant with his first wife was separate from his covenant with his 700th wife. A different Ranking means different covenants with distinct substances (1 Kings 11:3).

Covenantal Rules and Rewards/Retribution

Some covenants grant Rewards to the lesser party solely through the greater party’s kindness (2 Samuel 9:1–7). Others require the lesser party to follow specific Rules to receive Rewards or avoid Retribution (Deuteronomy 28:1–2, 15).

If covenants have different Rules, they are distinct covenants.

For instance, the Rule of “do this and live” (e.g., Leviticus 18:5; Galatians 3:12) differs from “live and do this” (e.g., Ezekiel 36:27; John 14:15), reflecting different ways of receiving covenantal Rewards. Different Rules indicate different substances and, thus, different covenants.

Some covenants, even with the same Ranking and Rules, have different Rewards/Retribution. For example, two covenants with the same bank, with identical Rules, may involve different properties. Same Ranking and Rules, yet different Rewards mean different covenants (Genesis 23:16–20; Jeremiah 32:9–12).

If covenants have different conditions, they have different substances and are distinct covenants (Deuteronomy 28:1–2, 15).

Covenantal Framework in Reformed Theology

Much ink has been spilled on this topic. While nuances exist, there is broad agreement among Reformed theologians that covenants are oath-bound arrangements comprising a Ranking, Rules, and Rewards/Retribution, sealed by Ratification (Hebrews 6:13–17; Psalm 89:3).

Ratification is essential. Without an oath, a covenant is not yet binding. There may be a sure promise of a future covenant, but it remains a promise until Ratification. For example, a marriage engagement is a promise, but the covenant begins with the oath ceremony, its Ratification (Galatians 3:15–17; Genesis 15:9–18).

Defining the Covenant of Grace

What is the Covenant of Grace? As the Westminster Larger Catechism (Q. 30) states, it is the oath-bound arrangement, ratified by God’s promise, that “brings the elect into a state of salvation” (Genesis 3:15; Romans 5:15–19; Titus 1:2).

Who is included in this covenant? As WLC 31 notes, it is “with Christ as the second Adam, and in Him with all the elect as His seed” (Galatians 3:16, 29; Romans 8:9).

Hermeneutical Principles

In examining this topic, we must apply the same hermeneutical principles used throughout Scripture. We recognize the genre of literature, such as covenants, and interpret accordingly (Luke 24:27; Hebrews 1:1–2).

Covenants may stand alone or be embedded within other literary forms.

We first identify the immediate context of each historical covenant: its Ranking, Rules, Rewards/Retribution, and Ratification (Exodus 24:3–8; 2 Samuel 23:5).

Next, we consider how the covenant fits into the broader redemptive narrative (Romans 15:4).

Finally, we analyze the apostles’ typological use of these texts to form our covenantal system (1 Corinthians 10:1–11; Galatians 4:21–31).

If we impose our conclusions on the initial analysis or adopt a metaphysic different from the apostles, we risk misinterpretation. This would reflect tradition rather than exegesis (Colossians 2:8).

Key Linguistic Terms

Two terms are vital for understanding historical covenants. When a new covenant is established, Scripture uses karat berit (“to cut a covenant”) (Genesis 15:18; Jeremiah 34:18). When an existing covenant is affirmed, we typically see heqim berit (“to establish/affirm a covenant”) (Genesis 6:18; Genesis 17:7).

Historical Covenants in God’s Plan

In fulfilling His eternal plan, God condescended to make a Covenant of Works with Adam (Genesis 2:15–17) (Romans 5:12–14).

• Ranking: God as sovereign, Adam as representative.

• Rules: Work, keep the garden, avoid the forbidden fruit (Genesis 2:15–17).

• Rewards/Retribution: Life for obedience, death for disobedience (Genesis 2:17).

• Ratification: God’s oath-bound commitment. Adam broke this covenant, and as humanity’s federal representative, he and his posterity faced its Retribution (Romans 5:12).

In Genesis 3:15, God promised to bring the seed of the woman to reverse the curse (Romans 16:20; Galatians 4:4).

With Noah, God promised to maintain order in creation (Genesis 9:8–17).

• Ranking: God as sovereign, Noah and creation as subjects.

• Rules: Be fruitful, have dominion (affirming Adamic Rules, heqim berit) (Genesis 9:1, 7).

• Rewards/Retribution: Preservation of the world, with Retribution for bloodshed (Genesis 9:5–6).

• Ratification: The rainbow as God’s oath (Genesis 9:12–13).

The Abrahamic Covenant

With Abraham, we see three specific Rewards: lineage, land, and lords, initially fulfilled in Canaan and ultimately in Christ (Genesis 12:1–3; 17:4–8; 22:17–18; Galatians 3:16).

In Genesis 12, God promises to make Abram a great nation, bless him, and bless all families through him. These were sure promises, but no oath was made, so no formal covenant existed (Genesis 12:1–3; Hebrews 6:13–15).

The oath comes in Genesis 15, where a covenant is karat. God reiterates His promise, Abram believes, and it is credited as righteousness (v. 6). God passes through the animals alone, accepting full responsibility (v. 18), ratifying the covenant (Genesis 15:6–21).

• Ranking: God as sovereign, Abraham and his descendants as subjects.

• Rules: God unilaterally guarantees the Rewards (Genesis 15:13–21).

• Rewards/Retribution: Lineage, land, and lords, with individuals subject to exclusion for disobedience (e.g., Genesis 17:14).

• Ratification: God’s oath through the animal ceremony (Genesis 15:17–18).

In Genesis 17, when Abram is 99, God says, “Walk before Me and be blameless, that I may make My covenant between Me and you” (v. 2). God expands the Reward to many nations and says, “I will establish [heqim] My covenant… for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and your offspring” (v. 7). Circumcision is the covenant sign, and individuals neglecting it face Retribution (v. 14). The corporate Rewards are secure, but individual participation requires adherence to the Rules, reflecting the covenant’s dual aspects (Genesis 17:1–14).

We must let the text guide our interpretation. While categories like conditional and unconditional covenants are helpful, the Abrahamic Covenant has both aspects: God guarantees corporate Rewards, but individuals must follow the Rules to partake, and some face Retribution (Genesis 17:9–14; 18:19).

Ranking, Rules, and Rewards/Retribution in the Abrahamic Covenant

• Ranking: God, Abraham, and his offspring (Genesis 17:7; 22:17–18).

• Rules: God secures corporate Rewards, but individuals must follow Rules (e.g., circumcision) or face Retribution (Genesis 17:9–14).

• Rewards/Retribution: A lineage (offspring and the Offspring), a land (Canaan and a heavenly country), and lords (kings and the King of kings). Disobedience leads to exclusion (Genesis 17:6–8, 14; Hebrews 11:8–10).

• Ratification: God’s oath in Genesis 15, affirmed in Genesis 17 (Genesis 15:17–18; 17:7–14).

The Abrahamic Covenant is gracious, as God ensures its fulfillment, yet it requires adherence to Rules, and those who fail to comply face Retribution (Genesis 17:9–14; Romans 4:11–13).

The Abrahamic Covenant is cut with Abraham and affirmed with Isaac and Jacob (Genesis 17:19–21; 26:2–5; 28:13–15).

The Mosaic Covenant

This is not the only divine-human covenant God cuts (karat). In fulfillment of Genesis 15:13–14, God rescues Abraham’s offspring from Egypt, remembering His covenant with the patriarchs (Exodus 2:24; 6:5; 12:40–41).

In Exodus 19, God says, “If you will indeed obey My voice and keep My covenant, you shall be My treasured possession… a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (vv. 5–6). This builds on the Abrahamic Covenant, as Israel remains under it (Exodus 19:3–8; Deuteronomy 7:7–9).

However, in Exodus 34:10 and Deuteronomy 5:2–3, a new covenant is karat at Horeb, distinct from the patriarchal covenant: “Not with our fathers did the Lord make this covenant, but with us” (Deuteronomy 5:3). The “fathers” are the patriarchs (Deuteronomy 4:31). Thus, Israel is under multiple covenants simultaneously (Exodus 34:10, 27–28; Deuteronomy 5:2–3).

• Ranking: God as sovereign, Israel as subjects.

• Rules: Obey God’s voice and keep His covenant (e.g., Ten Commandments, Deuteronomy 5) (Exodus 20:1–17; Deuteronomy 5:6–21).

• Rewards/Retribution: Treasured possession and priestly nation for obedience; curses for disobedience (Deuteronomy 28; Leviticus 26).

• Ratification: God’s oath at Sinai (Exodus 24:7–8).

The Rules aim to ensure Israel’s holiness (Deuteronomy 6:24–25). Joshua 23:14–16 affirms God’s faithfulness but warns that disobedience, such as idolatry, brings Retribution. Deuteronomy 27 and 29 note Israel’s lack of a circumcised heart (29:4) yet expect temporal obedience (Deuteronomy 10:16; 29:4).

Covenant lawsuits against the northern (Amos) and southern kingdoms (Jeremiah 2; 7:30) cite false worship, not uncircumcised hearts, as the basis for Retribution. While a circumcised heart is commanded of all image-bearers, the Mosaic Covenant’s Retribution focuses on external disobedience, not lack of saving faith (Amos 2:4–8; 5:21–27; Jeremiah 7:30–34).

Comparing the Abrahamic and Mosaic Covenants

The Abrahamic Covenant has dual aspects, while the Mosaic Covenant focuses on corporate obedience. Both involve the same Ranking (God and Israel) but have different Rules and Rewards/Retribution, indicating distinct substances (Exodus 19:5–6; Genesis 17:7–14; Galatians 3:17–18).

The Davidic Covenant

The Davidic Covenant (karat, 2 Samuel 7) involves:

• Ranking: God, David, and his obedient son (2 Samuel 7:12–16; Psalm 89:3–4).

• Rules: Obedience to God’s law (2 Chronicles 6:16; Psalm 132:11–12).

• Rewards/Retribution: A perpetual throne for obedience, fulfilled in Christ (Psalm 89:28–37; Luke 1:32–33); Retribution for disobedience (2 Samuel 7:14–15).

• Ratification: God’s oath to David (Psalm 89:3–4). Its distinct Rewards mark it as a separate covenant (Acts 13:22–23).

Distinct Covenants and Their Fulfillment

The Abrahamic, Mosaic, Davidic, and New Covenants are each established by karat berit, not as affirmations of a single covenant (Genesis 15:18; Exodus 34:10; 2 Samuel 7:12–16; Jeremiah 31:31–34). Allowing Scripture to define their terms, these are related yet distinct covenants, each finding fulfillment in Christ (Luke 24:44–47; 2 Corinthians 1:20). Their content—Ranking, Rules, Rewards/Retribution, Ratification—defines their substance, as Ursinus and the 2016 OPC report on republication affirm.

Some Westminster theologians suggest these covenants are administrations of a single Covenant of Grace, sharing the same substance. This view emphasizes redemptive continuity, but the distinct Ranking, Rules, and Rewards/Retribution of each covenant suggest they are separate, with unique roles in God’s plan, culminating in the New Covenant (Hebrews 8:6–13).

The New Covenant

Jeremiah 31:31–34 describes the New Covenant, explicitly karat berit, as distinct from the Mosaic Covenant:

• Ranking: God and the house of Israel/Judah (fulfilled in the elect, Romans 9:6–9) (Jeremiah 31:31–33; Romans 9:6–9).

• Rules: God writes His law on their hearts (Jeremiah 31:33; Ezekiel 36:26–27; Hebrews 8:10).

• Rewards/Retribution: All know God, and their sins are forgiven; no Retribution for covenant members, as God ensures fulfillment (Jeremiah 31:34; Hebrews 8:11–12; 10:14–18).

• Ratification: Christ’s blood (Luke 22:20; Hebrews 8:6; 9:15–22).

Unlike the Abrahamic, Mosaic, and Davidic covenants, which included elect and non-elect, the New Covenant is exclusively for those with circumcised hearts, provided by God (Ezekiel 36:26–27; John 6:37–39; Hebrews 8:10–12).

Obedience in the New Covenant

New Covenant members must obey (John 14:15), but God fulfills the Rules by granting a new heart and forgiveness through Christ (Hebrews 8:10–12; Ezekiel 36:26–27). Unlike prior covenants, all requirements for eternal Rewards are accomplished by God (Hebrews 10:10, 14; Philippians 2:13).

Continuity of Ranking

The Ranking remains consistent: God and Israel, from Abraham to Christ. However, the Rules and Rewards/Retribution differ, reflecting distinct substances (Romans 9:6–8; Galatians 3:16–18).

Old Testament Covenants and Faith

Old Testament saints (e.g., Adam, Abraham, Moses) believed God, and it was credited as righteousness (Genesis 15:6; Hebrews 11:24–26). However, their covenants did not provide the new heart required for faith. They pointed to the coming seed (Genesis 3:15), the Offspring (Galatians 3:16), and the eternal Priest (Hebrews 7:23–25).

Salvation of Old Testament Saints

Old Testament saints were saved by grace through faith, looking to the promised New Covenant (Hebrews 11:13; John 8:56). Their covenants, while gracious, could not justify sinners before God. They were typological, pointing to the New Covenant’s better Rewards (Hebrews 8:6).

Limitations of Old Testament Covenants

Old Testament covenants did not forgive sin or cleanse consciences in the heavenly tabernacle (Hebrews 10:1–4). Their sacrifices cleansed the flesh but required faith in the coming Messiah for eternal redemption. Saints received New Covenant benefits by faith in the promised Savior (Hebrews 9:15; Romans 3:25–26).

The New Covenant as the Covenant of Grace

Only the New Covenant provides the grace and faith that justify sinners (Romans 8:9; Hebrews 8:10–12). Old Testament saints were justified by faith in the future New Covenant, not their covenantal terms (Hebrews 11:13; Galatians 3:8).

Conclusion: Membership in the Covenant of Grace

Who is included in the Covenant of Grace? Every person given to the Son in eternity past, granted the new heart of the New Covenant (Ephesians 1:4; Romans 8:9; John 6:37–39). The New Covenant alone is the Covenant of Grace, fulfilling God’s redemptive plan for the elect (Jeremiah 31:31–34; Hebrews 8:6–13).

Works referenced (partial list):

Bavinck, Herman. Reformed Dogmatics, vol. 3 (Baker, 2006), 212–23.

Beale, G. K. A New Testament Biblical Theology (Baker, 2011), 14–30.

Coxe, Nehemiah. “A Discourse of the Covenants,” in Nehemiah Coxe & John Owen, Covenant Theology: From Adam to Christ (RBAP, 2005), 43–106.

Denault, Pascal. The Distinctiveness of Baptist Covenant Theology (Solid Ground, 2013), 75–92.

Gentry, Peter J., and Stephen J. Wellum. Kingdom through Covenant, 2nd ed. (Crossway, 2018).

Horton, Michael. Introducing Covenant Theology (Baker, 2009), 49–73.

Kline, Meredith G. By Oath Consigned (Eerdmans, 1968), 1–42.

Kline, Meredith G. The Structure of Biblical Authority (Eerdmans, 1972), 141–68.

Kline, Meredith G. Treaty of the Great King: The Covenant Structure of Deuteronomy: Studies and Commentary (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1963).

Koehler, Ludwig, and Walter Baumgartner. Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT), s.v. “כָּרַת/בְּרִית”.

Mendenhall, George E. Law and Covenant in Israel and the Ancient Near East (Pittsburgh: The Biblical Colloquium, 1955).

Murray, John. The Covenant of Grace (Tyndale, 1954), 67–93.

Orthodox Presbyterian Church. Report of the Committee to Study Republication (2016), 1–110.

Orthodox Presbyterian Church. Report of the Committee to Study Republication (2016), 51–110.

Owen, John. An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews, vol. 22 (Banner of Truth, 1991), on Hebrews 8.

Owen, John. An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews, vol. 22, on Hebrews 9–11.

Owen, John. An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews, vol. 22, on the efficacy of the New Covenant.

Owen, John. Works, vol. 12 (Banner of Truth, 1967), 67–104 (on the pactum salutis / Covenant of Redemption).

Renihan, Samuel. The Mystery of Christ, His Covenant & His Kingdom (Founders, 2019).

Robertson, O. Palmer. The Christ of the Covenants (P&R, 1980), 227–66.

Schreiner, Thomas R. Galatians (Zondervan, 2010), 217–25 (on Gal. 3:15–17).

Turretin, Francis. Institutes of Elenctic Theology, vol. 2 (P&R, 1994), 184–202.

Ursinus, Zacharias. Commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism (P&R, repr. 1992), 372–86.

VanGemeren, Willem A., ed. New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology & Exegesis (NIDOTTE), vol. 1, s.v. “berit (covenant).”

Vos, Geerhardus. Biblical Theology (Banner of Truth, 1975), 5–28 (on typology).

Vos, Geerhardus. Redemptive History and Biblical Interpretation (P&R, 1980), 3–15.

Vos, Geerhardus. The Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews (Eerdmans, 1956)